Multidisciplinarity unplugged: vernacular disciplinary architectures of International Studies

What came first: the disciplinary niche or the multidisciplinary approach to social problematic? Have we only just started listening to each other, or have we always been connected? Is the M-word bureaucratic jargon or an ancient vernacular?

As a linguistic and environmental anthropologist with a past in the earth sciences and a present in heritage studies, disciplinary identity is, at the very least, a shifty concept and experience. I have always struggled to introduce myself in academic settings and beyond, and have often witnessed my colleagues go through similar experiences in an (academic) world where every voice has got to fit within job descriptions and terms of employment. This post aims to situate familiar voices in unfamiliar terrains: colleagues chatting in corridors and canteens, students grappling with new courses and my own experiences of belonging, all assembled together in what may sparkle further debates and reflections.

‘What’ is multidisciplinarity?

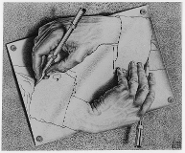

“What do we want it to be?”, stated one of my colleagues casually chatting in our department’s kitchen. Multidisciplinarity can be anything we want, but who is ‘we’? Who gets to define the term and to what extent is it not something already in practice? In an ensemble of disciplinary bridges, albeit Escherian, us disciplinary others were talking to each other about multidisciplinarity, and how to define it within International Studies, in such a multidisciplinary manner! Does the concept come before the experience or vice versa?

Consequently, I became more interested in our debating spaces (which were inherently multidisciplinary) and started wondering whether it would be more practical to look for multidisciplinarity in the places it had already been inhabiting since the programme’s inception: unplugged, unmanaged, undefined. Was it in the syllabi, in the lectures, in the tutorials, in our discussions, in our very practicing nature, in our daily administrative rituals? Would attempting to define it, ruin its pre-existing well-oiled machinery?

A very familiar monster: Student agency in multidisciplinary practice

From departmental corridors to the classroom; the easiest yet most challenging place to explore these topics were the different International Studies’ learning environments I was part of: International Politics tutorials, Global Political Economy lectures and Critical Heritage Studies seminars.

Coming from a variety of backgrounds, most of our students love a good debate! Nonetheless, a meta-discussion fresh from staff’s oven may feel unnecessary at times when mid-term exams are approaching and the ‘what do I need this for’ question seems to be the main motivator among students. However, after a few seconds of uncertainty, most students started thinking about what the M-word meant for them, and how it was already practiced. Some wondered whether studying regions of the world from a political, economic, historical, anthropological and linguistic perspective, would qualify them as experts in all those fields. Others voiced their worries as to whether all courses of the programme would cover the same topics and end up being repetitive. And most students stated that they knew what multidisciplinarity was but could not explain it. A disconnection between the experience of multidisciplinarity and the ability to define it seemed also present in the classroom.

After turning this broad discussion into active learning tools and playing ‘the name game’ and other role plays, students became more articulate about how different disciplines could approach a notion, a controversial issue, the understanding of regional systems, etc.

International Politics, Global Political Economy and Critical Heritage Studies are highly inter-disciplinary courses and fields of study. Together they assemble to provide more contextualized, critical and holistic understanding of world’s regions. A variety of topics and issues are analyzed and discussed using various methodological approaches, guided by the expertise of disciplinary and inter-disciplinary members of staff. At our programme, multidisciplinarity is not a label that has to substitute the interdisciplinary approaches of this programme’s courses, it is the very essence of the programme, which at the same time pre-exists and develops from its courses. It is all ultimately a process which, despite struggles to register the organic and fluid aspects of human agency, is not always easy to capture (fortunately!).

What are the frictions between contemporary conceptualizations of multidisciplinary and academic traditions?

As suggested in the previous section, there seems to be a disconnection between formalizing multidisciplinarity and experiencing it, and a time lapse between the former being made relevant as of late and the latter having pre-existed current trends to define it in education. Although, this is a manifold issue and a variety of features of today’s academic environments and relations feed into it, there is one aspect that seems to be key when it comes to multidisciplinarity in education: a challenging and challenged curriculum.

It took three centuries to formally lock science away from philosophy and into a specific epistemology by means of legitimizing the stand of different methods of enquiry and analysis. In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, European educational institutions used the term ‘discipline’ to catalogue (multiple) bodies of knowledge that challenged neo-classic theory and praxis in the secularization of universities. A revolutionary term at the time, it was later considered problematic by theorists like Foucault who explored the power relations these categories enabled and disabled. "The disciplines characterize, classify, and specialize; they distribute along a scale, around a norm, hierarchize individuals in relation to one another and, if necessary, disqualify and invalidate." (Foucault, 1975/1979, p 223).

The political dimensions of a paradigm shift into multidisciplinarity as key to innovation, technological development and tackling so-called societal challenges (modernizing European industries that had suffered from a fragmented market) was formally presented as part of the Innovation Union and in the European Framework Programmed (Horizon 2020 https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/). As ERC and other research funding bodies aim for multidisciplinarity by means of granting socio-economic growth, European universities have increasingly adopted such technocratic paradigms of multidisciplinarity as a new device to grant success in a variety of fields, such as research funding, marketing, ranking marker and as a feature of research’s excellence framework.

Contemporary managerial conceptualizations of education, the curriculum, and industry’s competitiveness, pose a threat to a more sophisticated understanding of how (multi) disciplinary expertise can work in an extremely diverse world, where euro-centric terminology and systems may not apply to daily life. At the same time, International Studies’ vernacular architecture of multidisciplinarity can sometimes rest too heavily on classic theorists.

Where can multidisciplinarity take us? Contextualizing the co-production of knowledge

Aside from formalized multidisciplinarity, vernacular mechanisms of simultaneity operate in study programmes, such as International Studies. These contemporary fields of enquiry promote a more critical approach to world’s relations and systems. However, the structure of the present curriculum can function as an obstacle towards reflexivity and critical approaches, as it still rests heavily on the so-called precursors of the disciplines focusing less on more contemporary and critical theorists and authors, presented as part of interdisciplinary courses.

Could critical approaches to contemporary multidisciplinarity itself help diversify the curriculum? Most definitely: by bringing the very debate on multidisciplinarity to the classroom, including student agency in the discussions about and the design of the very curriculum and its formalization. Questions and challenges are many, but possibilities are increasingly opening up new venues to communicate what we experience, how we experience it and where do we go from there.